The historic seminal book on orthopedics was written by Nicholas Andry in 1741 (1). The primary discussion of his book addressed the treatment of spinal distortions, beginning in childhood. Andry was a professor of medicine at the University of Paris.

The word orthopedic is a composite of two Greek words:

Ortho, meaning straight.

Pedic, meaning child.

Andry’s book emphasized the fact that children who did not grow straight had many health problems and a difficult life.

•••••••••

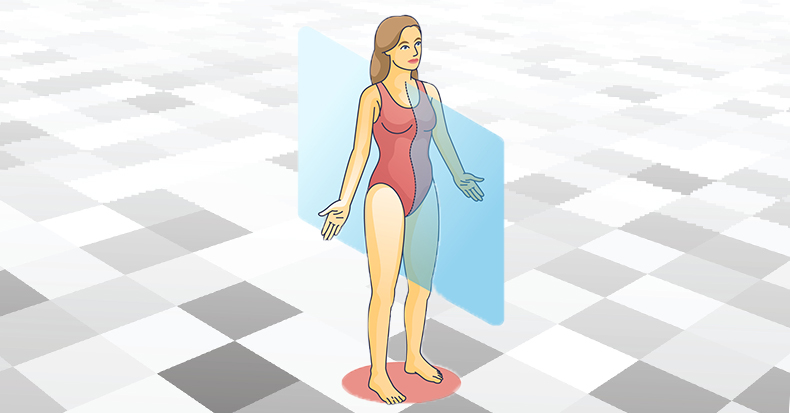

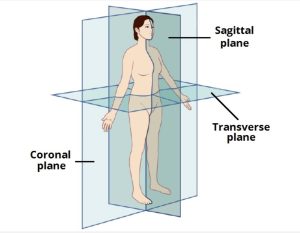

The sagittal plane divides the body into two equal halves.

Postural distortions that move the spine and head backwards along the sagittal plane are called posterior distortions. Postural distortions that move the spine and head forwards along the sagittal plane are called anterior distortions. The emphasis of this discussion is anterior postural distortions along the sagittal plane.

The primary emphasis of the chiropractic community, by far, is the treatment of spinal pain syndromes. This was detailed in the most comprehensive review of the chiropractic profession in the modern era (2). Ninety-three percent of patients who initially chose to see chiropractors did so because of a spinal pain complaint. There is no doubt that chronically altered posture is related to spinal musculoskeletal pain syndromes (3, 4).

Biomechanics

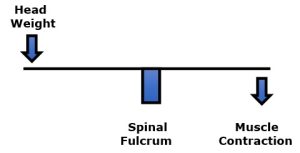

Upright posture is a first-class lever mechanical system, such as a teeter-totter or seesaw (5, 6). In the first-class mechanical system, the fulcrum is where the forces are the greatest. For upright human posture, the fulcrum is the vertebral column and its joints.

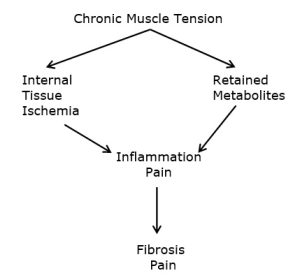

When a patient has anterior postural distortions along the sagittal plane, their head is projected forward of the fulcrum. Yet, the patient does not fall onto their face. Their muscles, on the opposite side of the fulcrum, will contract to balance the patient’s stance, but at a high price. The joints of the vertebral column (the fulcrum) are subjected to very high loads, accelerating joint breakdown, degeneration, irritations, inflammation, and pain. Simultaneously, the constant contraction of the posture balancing muscles causes muscle problems, including inflammation, fibrosis, and pain (7).

An example is presented by Rene Cailliet, MD (7). Dr. Cailliet notes that if one’s 10-pound head is anteriorly displaced along the sagittal plane by 3 inches, the required counter balancing muscle contraction on the opposite side of the fulcrum (the vertebrae) would be 30 lbs. (10 lbs. X 3 inches):

The constant muscle contraction required to balance anterior sagittal postural distortions creates muscle fatigue, inflammation, fibrosis, and eventually leads to chronic musculoskeletal pain syndromes (7). Collectively, these muscle syndromes are known as myofascial pain syndromes (8, 9, 10).

Modern Problems

There is a modern epidemic of poor posture, neck pain, shoulder pain, arm/hand neurological symptoms, and accelerated spinal degenerative arthritis. This modern trend is attributed to the excessive use of hand-held communication devices with the head/neck bent forward, or anterior postural distortions into the sagittal plane. Both lay media and professional publications have labeled this postural distortion as “Text Neck” or “Tech Neck.”

In 2017, Reuters Health published an article titled (11):

Leaning Forward During Phone Use May Cause ‘Text Neck’

This article makes the following points:

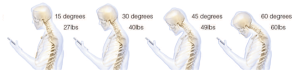

- People often look down when using their smartphones, particularly when texting.

- Studies have found that people hold their necks at around 45 degrees forward when using their smartphones.

- When in a neutral position looking forward, the head weighs about 10 to 12 pounds. At a 15-degree forward flexion position, it functions as if it weighs 27 pounds.

- At 60 degrees of forward flexion, the stress on the spine increases to about 60 pounds.

- These prolonged abnormal stresses on a growing spinal column may lead to abnormal spinal development with dire long-term spinal health consequences in adulthood.

- Spine surgeons are noticing an increase in patients with neck and upper back pain, likely related to poor posture during prolonged smartphone use.

- Young patients who should not have back and neck issues are reporting disk herniations and spinal alignment problems.

- “In an X-ray, the neck typically curves backward, and what we’re seeing is that the curve is being reversed as people look down at their phones for hours each day.”

- Simple lifestyle changes are suggested to relieve the stress from the “text neck” posture, including holding cell phones in front of the face while texting, and using two hands and two thumbs to create a more symmetrical and comfortable position for the spine.

- Also, people who work at computers or on tablets should use an elevated monitor stand so it sits at a natural horizontal eye level.

- Take frequent rest breaks and/or engage in some physical exercise that can strengthen the neck and shoulder muscles. Ex 1: Lie on a bed and hang one’s head backward over the edge, extending the neck to restore the normal arc in the neck. Ex 2: While sitting/standing, attempt to align the neck with the ears over the shoulders and the shoulders over the hips.

In 2018, The New York Post published an article titled (12):

Tech is Turning Millennials into a Generation of Hunchbacks

This article profiles a young man who began suffering from upper-back pain and neck soreness while in his late teens, subsequent to a habit of hunching over his cellular phone. As his symptoms progressed he developed constant pain, he hunched his shoulders, and the pain caused him to wake up numerous times throughout every night, causing constant fatigue. His upper back and neck would become incredibly tight; his neck was always bent forward.

After a decade of suffering, the young man’s chiropractor diagnosed him with “tech neck.” The loss or reversal of the normal cervical curve into the anterior sagittal plane is easily diagnosed with postural x-rays. The author notes:

“Undoing the damage is a process that includes breaking bad habits, taking standing breaks and doing exercises such as yoga, foam rolling and stretches that promote good carriage and strengthen core and upper body muscles. Experts also advise patients to hold mobile devices with their elbows at 180 degrees so the screen is in front of their faces.”

Treatment options include chiropractic, restorative postural traction, postural exercises, and core exercises.

In 2014, Kenneth K. Hansraj, MD, published an article in the journal Surgical Technology International, titled (13):

Assessment of Stresses in the Cervical Spine Caused by Posture and Position of the Head

Dr. Hansraj is Chief of Spine Surgery at the New York Spine Surgery & Rehabilitation Medicine facility. He notes that billions of people are using cell phone devices on the planet, essentially in poor posture. Consequently, the purpose of this study was to assess the forces incrementally seen by the neck (cervical spine) as the head is tilted forward into worsening forward head posture.

Dr. Hansraj indicates that an average person spends 2-4 hours a day with their heads tilted forward reading and texting on their smart phones / devices, amassing 700-1400 hours of excess, abnormal cervical spine stress per year. A high school student may spend an extra 5,000 hours in poor posture per year.

Dr. Hansraj created a cervical spine model to calculate the forces experienced by the cervical spine when in incremental flexion (forward head position). His mathematical analysis used a head weight of 13.2 pounds. His calculations are as follows:

Dr. Hansraj states:

“Poor posture invariably occurs with the head in a tilted forward position and the shoulders drooping forward in a rounded position.”

“The weight seen by the spine dramatically increases when flexing the head forward at varying degrees.”

“Loss of the natural curve of the cervical spine leads to incrementally increased stresses about the cervical spine. These stresses may lead to early wear, tear, degeneration, and possibly surgeries.”

Creepy Things

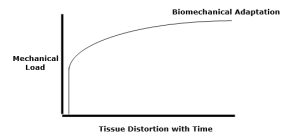

Biological soft tissues (ligaments, cartilage, tendons, muscles, etc.) adapt to prolonged postural distortions. Soft tissues literally change in response to these distortions. Over time they become longer or shorter in response to the positions they are habitually exposed to (14). The technical term for this premise is called viscoelastic creep (6).

Once soft tissues undergo viscoelastic creep, the correction of the postural distortion is no longer a simple thing. Neurological postural distortions are routinely improved quickly with chiropractic adjusting. However, the reversal of viscoelastic creep postural distortions are more complex. Creep distortions often respond best to both chiropractic adjusting and to rehabilitation programs that involve heel lifts, traction, correctional fulcrum blocks, tissue work, exercise, and more.

Associated biomechanical problems to having one’s head bent forward in the sagittal plane is a compensatory rigid upper thoracic spine hyperkyphosis and an overall forward leaning of the entire spinal column into the anterior sagittal plane. The relevance of both of these problems is detailed below.

A Review of Pertinent Studies

In 2004, the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society published a study titled (15):

Hyperkyphotic Posture Predicts Mortality in Older Community-Dwelling Men and Women: A Prospective Study

This was a prospective study that included 1,353 participants. Kyphotic posture was measured as the number of 1.7-cm blocks needed to be placed under the participant’s head to achieve a neutral head position when lying supine on a rigid radiology table. Individuals with hyperkyphosis cannot lie flat with their heads touching a flat surface unless they hyperextend their necks. Study participants were followed for an average of 4.2 years. Hyperkyphotic posture was specifically associated with an increased rate of death due to atherosclerosis. These authors note:

“Hyperkyphosis is associated with restrictive pulmonary disease and poor physical function, suggesting that hyperkyphosis might be associated with other adverse health outcomes.”

“With increasing kyphotic posture, there was a trend towards greater mortality.”

“For deaths due to atherosclerosis, participants with hyperkyphotic posture had a significant 2.4 times greater rate of death.”

“It is possible that hyperkyphotic posture reflects an increased rate of physiological aging.”

••••

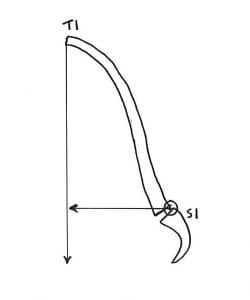

In 2005, the journal Spine published a study titled (16):

The Impact of Positive Sagittal Balance in Adult Spinal Deformity

The authors measured the pain, systemic health, and disability status of 298 individuals and compared such measurements to a radiographic measurement of sagittal plane postural balance. A full-spine (36 inch) lateral x-ray was exposed. A plum line was dropped from the body of the C7 vertebrae and measured with respects to the articulating surface of L5 with the sacral base. All measures of health status showed significantly poorer scores as C7 plumb line deviation increased in the forward direction (anterior to the sacral base). The authors note:

“Patients with relative kyphosis in the lumbar region had significantly more disability than patients with normal or lordotic lumbar sagittal measures.”

“This study shows that although even mildly positive sagittal balance is somewhat detrimental, severity of symptoms increases in a linear fashion with progressive sagittal imbalance.”

“There was clear evidence of increased pain and decreased function as the magnitude of positive [forward] sagittal balance increased.”

“This study shows that although even mildly positive [forward] sagittal balance is somewhat detrimental, severity of symptoms increases in a linear fashion with progressive [forward] sagittal imbalance.”

••••

In 2013, The Journals of Gerontology: Series A: Biological Sciences published a study titled (17):

Spinal Posture in the Sagittal Plane is Associated with Future Dependence in Activities of Daily Living

The authors measured spinal postures in 804 older adults (aged 65–94 years) to determine if anterior sagittal postures were associated with the need for future assistance in Activities of Daily Living (ADL). They found that anterior sagittal posture that pitched the body and head forward was significantly associated with the need for future assistance in the person’s Activities of Daily Living. The authors state:

“Accumulated evidence shows how important spinal posture is for aged populations in maintaining independence in everyday life.”

“Spinal posture changes with age, but accumulated evidence shows that continued good spinal posture is important in allowing the aged to maintain independent lives.”

“Declines in balance and gait skills caused by inclination lead to falls and fractures, and that these negative outcomes in turn lead to dependence in ADL among elderly people.”

“Even mildly positive sagittal balance is somewhat detrimental, the decline in health status increases in a linear fashion with progressive sagittal imbalance.”

“[The] results indicate that attention needs to be paid to inclination in spinal posture to identify elderly people at high risk of becoming dependent in ADL.”

••••

In 2022, the journal BMJ Open published a study titled (18):

Association of Kyphotic Posture with Loss of Independence and Mortality in a Community-Based Prospective Cohort Study

The objective of this study was to investigate the association between anterior sagittal kyphotic posture and future loss of independence and mortality in community-dwelling older adults. It is a prospective study that assessed 1,621 community-dwelling adults aged ≥65 years at the time of their baseline health check-up. Subjects were prospectively followed for a medium of 5.8 years. The authors note:

“There has been a growing concern regarding the association between kyphotic posture and serious health-related outcomes, such as loss of independence and mortality.”

“Kyphotic posture was associated with loss of independence and mortality in community-dwelling older adults.”

The authors note that the deleterious effects of kyphotic posture on health include:

- A decline in physical function

- Impairment in pulmonary function

- Increased pain

- Gastro-esophageal reflux disease

- Poor quality of life

- Increase in falls

••••

Also, in 2022, the journal Scientific Reports published an article titled (19):

Detection of Cognitive Decline by Spinal Posture Assessment in Health Exams of the General Older Population

The authors analyzed cognitive function test scores as determined by Montreal Cognitive Assessment and Mini-Mental State Examination tests in 411 subjects and compared the scores to their anterior sagittal spinal balance. The authors noted:

“Spinal balance anteriorization can be regarded as an easily visible indicator of latent cognitive decline in community-dwelling older people.”

“Visible clues as to the anteriorization of spinal balance can help to more easily monitor for signs of impending cognitive impairment, which may lead to dementia and frailty.”

“Our results showed that the anteriorization of spinal balance existed at the onset of cognitive impairment.”

“When visible appearance changes in posture occur, appropriate diagnostic measures are advised in consideration of the possibility of cognitive impairment to help prevent frailty, dementia, and bedridden status.”

The authors suggest that improvements in anterior sagittal plane postural distortions may reduce the incidence and progression of cognitive decline.

••••

Chiropractors have always understood the adverseness of postural distortions and especially a forward shift in sagittal spinal alignment. A number of chiropractic techniques are primarily concerned with assessing, preventing, and changing these and other postural distortions. The chiropractic interventions used often involve combinations of certain spinal adjustments (specific manipulations), ergonomic advice, spinal exercises, and extension (mirror image reversal) traction. These techniques are taught at both the chiropractic university/college level as well as in post-graduate classes. A handful of the published outcomes on these chiropractic approaches for the management of anterior sagittal postural distortions are referenced here (20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28).

REFERENCES

- Biedermann H; Manual Therapy in Children; Churchill Livingstone; 2004.

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults: Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

- Kendall HO, Kendall FP, Boynton DA; Posture and Pain; Williams and Wilkins; 1985.

- Mennell JM; “The Forward Head Syndrome” in The Musculoskeletal System, Differential Diagnosis from Symptoms and Physical Signs; Aspen; 1992.

- Cailliet R; Low Back Pain Syndrome; 4th edition; FA Davis Company; 1981.

- White AA, Panjabi MM; Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine; Second Edition; Lippincott; 1990.

- Cailliet R; Soft Tissue Pain and Disability; 3rd Edition; FA Davis Company; 1996.

- Travell J, Simons D; Myofascial pain and dysfunction, the trigger point manual; New York: Williams & Wilkins; 1983.

- Travell J, Simons D; Myofascial pain and dysfunction, the trigger point manual: THE LOWER EXTREMITIES; New York: Williams & Wilkins; 1992.

- Simons D, Travell J; Travell & Simons’, Myofascial pain and dysfunction, the trigger point manual: Volume 1: Upper Half of Body; Baltimore; Williams & Wilkins; 1999.

- Carolyn Crist C; Leaning forward during phone use may cause ‘text neck’; Reuters Health; April 14, 2017.

- Fleming K; Tech is Turning Millennial into a Generation of Hunchbacks; The New York Post; March 5, 2018.

- Hansraj KK; Assessment of Stresses in the Cervical Spine Caused by Posture and Position of the Head; Surgical Technology International; November 2014; Vol. 25; pp. 277-279.

- Bowman K; Move Your DNA: Restore Your Health Through Natural Movement;

- Kado DM, Huang MH, Karlamangla AS, Barrett-Connor E, Greendale GA; Hyperkyphotic Posture Predicts Mortality in Older Community-Dwelling Men and Women: A Prospective Study; Journal of the American Geriatrics Society; October 2004; Vol. 52; No. 10; pp. 1662-1667.

- Glassman SD, Bridwell K, Dimar JR, Horton W, Berven S, Schwab F; The Impact of Positive Sagittal Balance in Adult Spinal Deformity; Spine; September 15, 2005; Vol. 30; No. 18; pp. 2024-2029.

- Kamitani K, Michikawa T, Iwasawa S, Eto N, Tanaka T, Takebayashi T, Nishiwaki T; Spinal Posture in the Sagittal Plane is Associated with Future Dependence in Activities of Daily Living: A Community-Based Cohort Study of Older Adults in Japan; The Journals of Gerontology: Series A: Biological Sciences; July 2013; Vol. 68; No. 7; pp. 869-875.

- Hijikata Y, Kamitani T, Sekiguchi M, Otani K, Fukuhara S, Konno S, Takegami M, Yamamoto Y; Association of Kyphotic Posture with Loss of Independence and Mortality in a Community-Based Prospective Cohort Study: The Locomotive Syndrome and Health Outcomes in Aizu Cohort Study; BMJ Open; March 31, 2022; Vol. 12; No. 3; e052421.

- Nishimura H, Ikegami S, Uehara M, Takahashi J, Tokida R, Kato H; Detection of Cognitive Decline by Spinal Posture Assessment in Health Exams of the General Older Population; Scientific Reports; May 19, 2022; Vol. 12; No. 1; pp. 8460.

- idealspine.com.

- Leach RA; An evaluation of the effect of chiropractic manipulative therapy on hypolordosis of the cervical spine; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; March 1983; Vol. 6; No. 1; pp. 17-23.

- Harrison DD, Jackson BL, Troyanovich S, Robertson G, de George D, Barker WF; The Efficacy of Cervical Extension-Compression Traction Combined with Diversified Manipulation and Drop Table Adjustments in the Rehabilitation of Cervical Lordosis: A Pilot study; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; September 1984; Vol. 17; No. 7; pp. 454-464.

- Troyanovich SJ, Harrison DE, Harrison DD; Structural rehabilitation of the spine and posture: Rationale for treatment beyond the resolution of symptoms; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; January 1998; Vol. 21; No. 1; pp. 37-50.

- Harrison DE, Harrison, DD, Haas JW; CBP Structural Rehabilitation of the Cervical Spine; 2002.

- Harrison DE, Cailliet R, Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Holland B; A new 3-point bending traction method for restoring cervical lordosis and cervical manipulation: A nonrandomized clinical controlled trial; Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation; April 2002; Vol. 83; No. 4; pp. 447-453.

- Morningstar MW, Strauchman MN, Weeks DA; Spinal manipulation and anterior headweighting for the correction of forward head posture and cervical hypolordosis: A pilot study; Journal of Chiropractic Medicine; Spring 2003; Vol. 2; No. 2; pp. 51-54.

- Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Betz JJ, Janik TJ, Holland B, Colloca CJ, Haas JW; Increasing the cervical lordosis with chiropractic biophysics seated combined extension-compression and transverse load cervical traction with cervical manipulation: nonrandomized clinical control trial; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; March-April 2003; Vol. 26; No. 3; pp. 139-2151.

- Ferrantelli JR, Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Stewart D; Conservative treatment of a patient with previously unresponsive whiplash-associated disorders using clinical biomechanics of posture rehabilitation methods; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; March-April 2005; Vol. 28; No. 3; pp. e1-8.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”